FITTING IN EYEGLASS FRAMES

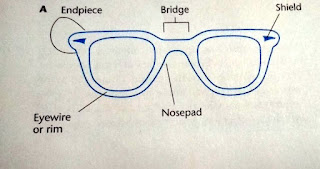

Eyeglass Frames comes in a variety of sizes, shapes, styles, and materials, all of which have become influenced by fashion as well as the personal preferences of patients. Naturally, most patients try to choose frames that they feel are becoming to their appearance. However, opticians, ophthalmic medical assistants, and others who help patients choose frames and wear them comfortably also must consider frames from the aspect of their tilt and curve in relationship to the wearer's face, and their overall size and shape (both of which can affect proper peripheral vision), as well as their comfortable fit. Fig 1.1 shows the principal parts of a typical frame.

The pantoscopic angle of an eyeglass frame is the angle by which the frame front deviates from the vertical plane when the glasses are worn on the face. The pantoscopic angle is estimated by viewing the eyeglasses on the face from the side (Fig 1.2). The lower rims of the frame front normally are closer to the cheeks than are the upper rims. A usual pantoscopic angle ranges from 4* to 18* (the average pantoscopic angle is 15*), although an individual with protruding eyebrows may exceed this range. The term retroscopic tilt is used to describe eyeglasses that are adjusted so that the lower rims tilt away from the face; this happens only rarely by design but can occur in error.

A proper pantoscopic angle allows the eye to rotate downward from the distance gaze to the near gaze while maintaining a similar vertex distance. Patients can have visual problems that may prompt an office visit if a retroscopic tilt is present or if the pantoscopic angle is incorrect; patients with moderate cylinder powers and above-average refractive errors have more problems and notice this improper tilt.

Some patients choice of frame sizes and shapes may be restricted because of their lens prescriptions. If the eyeglass prescription is moderate to high (that is, approximately 3 dioptres or more of myopia or hyperopia), frame size and shape play a significant role in altering peripheral vision. This problem primarily relates to the increase in vertex distance from the center of the lens to the edge of the lens. For larger lenses, the increase in vertex distance at the edge of the lens compared to the center may dramatically change both the spherical and the cylindrical components of the optical prescription. Moreover, the farther from the center of the lens, the greater the optical disortion. Large lenses may be fashionable, but they may cause significant optical aberration in the peripheral parts of the lens.

EFFECTS ON PATIENT COMFORT:

A patient who requires eyeglasses will not conscientiously wear them if the frames fit poorly, even though the prescription may be correct. Misaligned frames or improper frame size can cause the following problems:

a. Frames slide forward.

b. Frames fit loosely.

c. Frames must be positioned awkwardly to see properly.

d. Frame temples create pressure on the side of the head or at the ears.

e. Eyelashes or eyebrows touch the lenses.

When fiting or adjusting the fit of a pair of eyeglasses, pay special attention to the physical structure of a patient's face. Because most of the weight of the eyeglasses is placed on the bridge of the patient's nose, the weight should be evenly distributed. Once ear may be slightly higher than the other ear; therefore, the fit over or behind each ear should be carefully made. The nature of the individual's skin (for eg, the degree of oiliness) may cause some types of frames to slip down from the bridge of the nose. No easy formula exists for adjusting a pair of glasses so that the patient will wear them, but thorough observation and listening carefully to what a patient says will allow you to help the patient choose frames appropriately and wear them comfortably.

When checking the fit or assessing other problems, take special care when putting the eyeglasses on the patient or taking them off. Always cover the tips of the temple pieces (also called temples) with your fingers until you have moved them past the patient's eyes. This procedure avoids poking the patient in the eye with the pointed ends of the frame temples.

CARE OF EYEGLASSES:

Eyeglass lenses and frames, especially those worn daily, are subject to considerable wear and tear. Although most frames and lenses are designed to take a certain amount of abuse, patients can get much longer, more satisfying wear out of their eyeglasses if they receive instructions in proper cleaning and handling.

A variety of cleaning sprays and special cloths exist for cleaning eyeglass lenses. For the most part, however, these products may be needed only if the lenses have been specially treated, such as with anti-reflection, scratch-resistant, or color coatings. Patients can keep their glasses clean without damaging lens surfaces by using proper cleaning methods and materials. Conventional glass or plastic lenses can be cleaned simply with soap and water, then dried with a soft cloth. All lenses should be cleaned while wet; rubbing a cloth or tissue over dry lenses may drag dirt across the lens surfaces and scratch them.

When appropriate, the ophthalmic medical assistant should instruct patients in the proper method of cleaning their eyeglass lenses. Patients should also be instructed to protect their eyeglasses from impact or pressure by storing them in the eyeglass case when not in use. The assistant may also caution patients that when placing eyeglasses on a surface, they should place the side with the temple pieces down so that the lenses will not be scratched. Plastic lenses are more susceptible to scratching than glass lenses.

Eyeglass Frames comes in a variety of sizes, shapes, styles, and materials, all of which have become influenced by fashion as well as the personal preferences of patients. Naturally, most patients try to choose frames that they feel are becoming to their appearance. However, opticians, ophthalmic medical assistants, and others who help patients choose frames and wear them comfortably also must consider frames from the aspect of their tilt and curve in relationship to the wearer's face, and their overall size and shape (both of which can affect proper peripheral vision), as well as their comfortable fit. Fig 1.1 shows the principal parts of a typical frame.

Fig. 1.1. Anatomy of an Eyeglass Frame A) Front View of Frame B) Side View temple piece C) Top view of Frame Front

The pantoscopic angle of an eyeglass frame is the angle by which the frame front deviates from the vertical plane when the glasses are worn on the face. The pantoscopic angle is estimated by viewing the eyeglasses on the face from the side (Fig 1.2). The lower rims of the frame front normally are closer to the cheeks than are the upper rims. A usual pantoscopic angle ranges from 4* to 18* (the average pantoscopic angle is 15*), although an individual with protruding eyebrows may exceed this range. The term retroscopic tilt is used to describe eyeglasses that are adjusted so that the lower rims tilt away from the face; this happens only rarely by design but can occur in error.

Fig 1.2 Pantoscopic angle estimated by viewing the eyeglasses on the face from the side

A proper pantoscopic angle allows the eye to rotate downward from the distance gaze to the near gaze while maintaining a similar vertex distance. Patients can have visual problems that may prompt an office visit if a retroscopic tilt is present or if the pantoscopic angle is incorrect; patients with moderate cylinder powers and above-average refractive errors have more problems and notice this improper tilt.

Some patients choice of frame sizes and shapes may be restricted because of their lens prescriptions. If the eyeglass prescription is moderate to high (that is, approximately 3 dioptres or more of myopia or hyperopia), frame size and shape play a significant role in altering peripheral vision. This problem primarily relates to the increase in vertex distance from the center of the lens to the edge of the lens. For larger lenses, the increase in vertex distance at the edge of the lens compared to the center may dramatically change both the spherical and the cylindrical components of the optical prescription. Moreover, the farther from the center of the lens, the greater the optical disortion. Large lenses may be fashionable, but they may cause significant optical aberration in the peripheral parts of the lens.

EFFECTS ON PATIENT COMFORT:

A patient who requires eyeglasses will not conscientiously wear them if the frames fit poorly, even though the prescription may be correct. Misaligned frames or improper frame size can cause the following problems:

a. Frames slide forward.

b. Frames fit loosely.

c. Frames must be positioned awkwardly to see properly.

d. Frame temples create pressure on the side of the head or at the ears.

e. Eyelashes or eyebrows touch the lenses.

When fiting or adjusting the fit of a pair of eyeglasses, pay special attention to the physical structure of a patient's face. Because most of the weight of the eyeglasses is placed on the bridge of the patient's nose, the weight should be evenly distributed. Once ear may be slightly higher than the other ear; therefore, the fit over or behind each ear should be carefully made. The nature of the individual's skin (for eg, the degree of oiliness) may cause some types of frames to slip down from the bridge of the nose. No easy formula exists for adjusting a pair of glasses so that the patient will wear them, but thorough observation and listening carefully to what a patient says will allow you to help the patient choose frames appropriately and wear them comfortably.

When checking the fit or assessing other problems, take special care when putting the eyeglasses on the patient or taking them off. Always cover the tips of the temple pieces (also called temples) with your fingers until you have moved them past the patient's eyes. This procedure avoids poking the patient in the eye with the pointed ends of the frame temples.

CARE OF EYEGLASSES:

Eyeglass lenses and frames, especially those worn daily, are subject to considerable wear and tear. Although most frames and lenses are designed to take a certain amount of abuse, patients can get much longer, more satisfying wear out of their eyeglasses if they receive instructions in proper cleaning and handling.

A variety of cleaning sprays and special cloths exist for cleaning eyeglass lenses. For the most part, however, these products may be needed only if the lenses have been specially treated, such as with anti-reflection, scratch-resistant, or color coatings. Patients can keep their glasses clean without damaging lens surfaces by using proper cleaning methods and materials. Conventional glass or plastic lenses can be cleaned simply with soap and water, then dried with a soft cloth. All lenses should be cleaned while wet; rubbing a cloth or tissue over dry lenses may drag dirt across the lens surfaces and scratch them.

When appropriate, the ophthalmic medical assistant should instruct patients in the proper method of cleaning their eyeglass lenses. Patients should also be instructed to protect their eyeglasses from impact or pressure by storing them in the eyeglass case when not in use. The assistant may also caution patients that when placing eyeglasses on a surface, they should place the side with the temple pieces down so that the lenses will not be scratched. Plastic lenses are more susceptible to scratching than glass lenses.

Comments

Post a Comment